Think you know what to do to protect your intellectual property?

Think again.

The Internet’s spawned more than a couple of myths about copyright, creating widespread misunderstanding of author rights.

As authors, we care about our ideas and characters — and we want to protect them outside of our pages. That’s when copyright laws step in.

Here are four questions about copyright to which you want to know the answers right now, so that they don’t trip you up, even after you’ve written “The End.” (A/N: the below information applies only to the U.S. copyright system.)

Ready?

What is poor man’s copyright?

Poor man’s copyright is the ghost that just will not go away.

To wit, the idea is this: instead of registering your copyright with the U.S. Copyright Office, you can prove your copyright by mailing yourself a copy of your manuscript, in a sealed envelope.

Presumably, this would give you:

1. proof of rightful ownership; and

2. a date stamp that would confirm to the judge the date on which you’d claimed copyright.

Best of all, poor man’s copyright only costs a total of $0.30, give or take a couple of cents if you splurge on an expensive postal stamp.

It sounds wonderful, right? It does not work. It is a total myth.

Some sites insist on telling writers that this is the way to go. In reality, if a copyright dispute was ever to arise, an argument involving poor man’s copyright would be quickly shot down. (How? Any competent attorney would point out that anyone can always send an unsealed envelope to themselves, slip in their manuscript in the future, and then seal the envelope.)

Don’t trust me? Poor man’s copyright is such a bad but widespread tactic that the U.S. Copyright Office itself issued this statement, debunking it once and for all:

“There is no provision in the copyright law regarding any such type of protection, and [poor man’s copyright] is not a substitute for registration.”

If you want to prove ownership over your work, it’s best to go the official route and register your work with the U.S. Copyright Office. More on that in a bit.

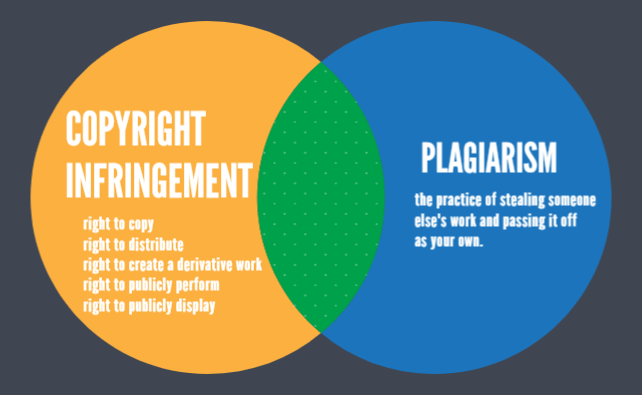

Is plagiarism identical to copyright infringement?

So, we all know that plagiarism is bad, right? Copyright infringement is no good, either.

But what exactly is the difference between the two?

Has a teacher ever told your class not to copy something from a source without proper attribution? That’s plagiarism. It occurs when you use someone’s work without proper credit, or when you present someone else’s work as your own. Plagiarism is a matter of ethics, and is enforced primarily by academic institutions and professors.

Copyright infringement, on the other end, is a legal matter — something that can only be settled in court. Copyright itself grants the creator of an original work five exclusive rights:

1. the right to distribute

2. the right to copy

3. the right to display the work publicly

4. the right to perform the work publicly

5. the right to create a derivative work

In short: when you infringe upon any of the above five rights, that’s copyright infringement. As you might’ve guessed, sometimes plagiarism and copyright intersect — but not all the time.

Since I find examples very useful, I’ve provided some below to illustrate the similarities and differences for you:

- When would plagiarism and copyright infringement intersect?

Publishing someone else’s blog post and claiming that you wrote it yourself. - What would constitute plagiarism, but not copyright infringement?

Copying a couple of paragraphs from Darwin’s Origin of Species into a report, without attribution. But because Origin of Species is in the public domain, no-one can accuse you of infringing on copyright. - What would constitute copyright infringement, but not plagiarism?

Printing and distributing copies of someone else’s play. Though you’re not claiming credit for the play, you are infringing on copyright by making copies without permission.

And here’s a handy summary

Is copyright registration mandatory?

Another common myth on the internet is that an author actually needs to copyright their work.

To put it gently: that’s nonsense!

You don’t need to “copyright a work,” as they say. Your work is protected under copyright the moment you create it. Suppose you write, “The bats did not roll the cats because they were not bats.” Well, you own the copyright to it the instant you put that pen to paper.

What you may want to do is register the copyright to your work.

Your book is your intellectual property — and registration gives you maximum protection over it. Once you register your copyright, you gain the ability to sue the perpetrator if copyright infringement ever occurs.

In a nutshell, copyright registration empowers you to assert your rights, when needed.

Copyright registration isn’t mandatory. In fact, Leo Babauta once wrote an article right on Write To Done that espoused uncopyrighting altogether. He argued that copyright is a barrier in today’s digital age that stops ideas from spreading — and that, consequently, authors should release their copyright on all their works.

Of course, that’s a bit of a non-traditional take. Though Leo’s arguments deserve a read, it ultimately depends on your risk appetite. If your goal is to protect your hard-earned intellectual property, is it advisable for you to register the copyright to your books? Yes.

If you want to find out more about your rights, I suggest that you check out this guide on How To Copyright A Book, which covers everything you need to know about registering your copyright.

Is fanfic considered copyright infringement?

If so, prayers up for 50 Shades of Grey, which EL James first published on the Internet under the pseudonym “Snowqueens Icedragon,” no?

But, in fact, where fanfiction resides on the spectrum of copyright infringement is not so clear.

Legal issues with fanfiction arise due to one of the rights that copyright protects: the creator’s exclusive right to create derivative works. In the past, fanfic writers have brought out Fair Use — a doctrine that provides an exception to copyright law for certain creative works, including commentary, parody, etc. — as a means of defense, to some success.

Of course, it must be said that many authors will not chase you into court (waving shiny pitchforks) for writing fanfiction. Creators such as J.K. Rowling and Joss Whedon give the practice their blessings, as far as it remains a non-commercial activity that isn’t “being published in the strict sense of traditional print publishing.”

But sometimes you get authors such as Anne Rice, who issued this statement in 2009: “I do not allow fanfiction. The characters are copyrighted. It upsets me terribly to even think about fanfiction with my characters.”

So our word of advice is to be smart about it. If you write fanfic for a certain fandom, be aware of the creator’s feelings about it, and react accordingly.

And if you should ever get sued for your fanfic, this is what you should know: the more transformative a work of fanfic is, the stronger your case for Fair Use becomes, in the courtroom.

Legal Myths for Authors Debunked for good

So, there you have it! Now you can walk back out into the book world, much better armed to protect your intellectual property. Having this knowledge in the back of your mind can give some peace of mind and allow you to focus on the biggest priority of all: writing your book.

What’s your experience with copyright? If you’re self-published, how did you arrive at your decision to register your copyright (or not)? Share your thoughts with us in the comments below.